Researched by: Credit Suisse

Executive Summary

Peru’s General Law of the Financial and Insurance Systems is vital for domestic financial system and also for the country’s social and economic development as a whole. The Peruvian Superintended of Banks, Insurance and AFPs (i.e. SBS) which plays a regulatory and supervisory role in the Peruvian financial system, has adopted major measures to improve the legal framework for Microfinance activities, which cover financial consumer protection, transparency and privacy of client data. From the SBS perspective, financial capability is the bedrock to contribute the social and economic developments of the nation.

Introduction

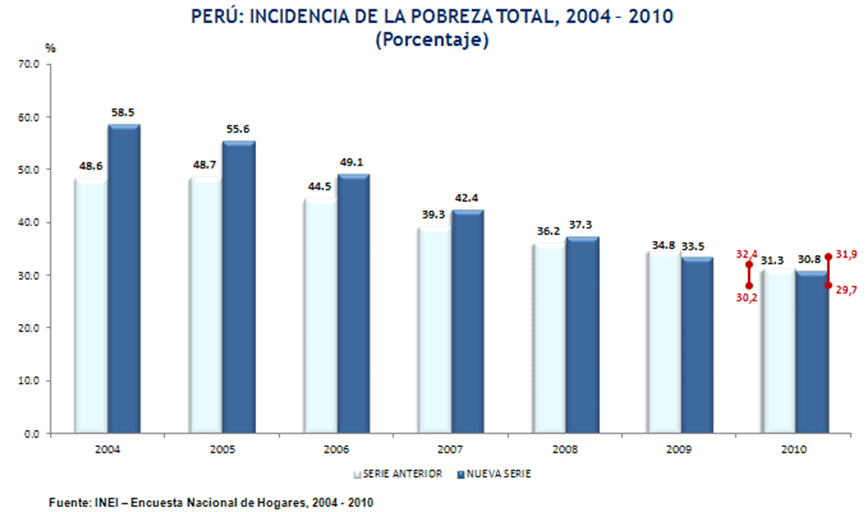

Peru is an emerging, market-oriented economy characterized by mineral wealth, which ranks fifth worldwide in gold production, second in copper and is among the top 5 producers of lead and zinc. Over the past decade, hiking prices in mineral commodities have driven the Peruvian economy growing at a rate of 7-9% per annual. The fastest increasing economy has offered great opportunities to the poor as well. Poverty has steadily decreased in nearly 20% since 2004 when almost half of the national population was under the poverty line (i.e. US$1.25 per day). The 2010 data shows that approximately 30% of its population is poor.

Since microcredit initiatives emerged in Peru in the 1970s, with a target of low-income women, the microfinance sector has been highly developed. Based on the 2011 data from SBS, microfinance gross loan portfolio has grown fifteen folds for the past ten years. Peru has the largest Microfinance sector in Latin America. Buoyed by an excellent legal framework, sophisticated regulators and a dedicated government to expand financial inclusion to the poor, Peru has ranked atop in 2001 for a third straight year by the annual Economist Intelligence Unit survey of world’s best business environments for microlending.

Who’s Who – Microfinance Sector in Peru

Practitioners

According to information from Association of Microfinance Institutions of Peru (Asociación de Instituciones de Microfinanzas del Perú, ASOMIF Perú), the Peruvian Microfinance sector has regulated and non-regulated Microfinance Institutions (MFIs). Only regulated entities must comply with auditing and reporting which are on a monthly basis and with strict loan loss provision stipulated by SBS.

- Cajas Municipales de Ahorro y Crédito (CMACs), established in 1980, are municipal savings and credit institutions and owned by local governments. Except of benefiting from a long international partnership with the German Sparkässe, they are able to offer a wide range of savings and credit products, as well as some public services mostly to urban client. CMACs, thus, have been the largest and most profitable non-bank formal MFIs.

- Cajas Rurales de Ahorro y Crédito (CRACs), founded in 1994, are rural savings and credit institutions and owned by private entrepreneurs to increase the supply of credit to small agricultural producers. The 1992 financial reforms closed the Agrarian Bank, which provided CRACs with opportunities to get larger exposure to agriculture and livestock sectors.

- EDPYMEs, created in 1996, are credit institutions which derived from Microfinance NGOs into the regulated sector. The incentives for NGOs to become EDPYMEs are that they would be exempt of the value added tax (IGV) and be able to manage funds from COFIDE, specifically addressed to micro-entrepreneurs. EDPYMEs are clearly oriented toward the financing of small and microenterprises, mostly in the urban context. EDPYMEs are not authorized to collect savings, but allowed to offer a wide range of credit products.

- Commercial banks, such as Mibanco, the first MFI fully equipped with a banking license, originated in 1998 from the NGO Acción Crediticia del Perú, with strong supports from the government. Its milestone was to acquire Financiera Crear, an Arequipa based financial company, by Compartamos Banco, a Mexico’s leading MFI. As of 2011, it served 420,000 credit clients and 260,000 savings clients.

- Cooperativas de Ahorro y Crédito (CACs), registered with, but not regulated by the SBS. CACs share their information on a voluntary basis with the Consortium for Private Organizations Promoting the Development of Small and Medium Enterprises, known as the Spanish short form COMPEME.

Regulators and Supervisors

SBS: guarantees economic and financial stability of individuals and corporations, enforces legal, regulatory and statutory regulations governing their activities, controls all of their transactions and businesses, such as file criminal claims against unauthorized individuals and corporations practicing the activities set forth in the General Law No. 26702, close their offices and requests the dissolution and liquidation of the violator if applicable.

Consumer protection and market conduct analysis have been fully incorporated into SBS’s functions and its organizational structure. SBS starts with an assumption that consumers have little and sometimes no negotiating power when financial service providers approach to them. The objective is to foster behaviors that minimize the information asymmetry between client and providers.

INDECOPI – The Consumer Protection Agency

According to the General Consumer Protection Law, INDECOPI, through its tribunal for the Defence of Competition and Intellectual Property, has enforcement powers over rules pertaining to competition, consumer protection and intellectual property rights in all sectors and industries including financial services. Such powers include the authority to conduct investigations, impose corrective measurements and levy sanctions.

INDECOPI is to resolve the disputes at the initial stage between consumers and providers and an alternative to the judiciary, since consumers can seek the judiciary only after going through INDECOPI’s dispute resolution process. Moreover, the judiciary may be perceived by many customers as slow and unpredictable and possibly not an efficient manner to solve the disputes.

INDOCOPI’s and SBS’s mandates might overlap to a certain extent, but in practice the two agencies have a well-defined division of labour in enforcement and a good level of coordination and information sharing. SBS concentrates on preventing wrongdoings and does not solve individual disputes between clients and providers. INDECOPI focuses its attention on corrective actions, which is, solving problems and disputes between a customer and a service provider.

Available Laws

Microfinance Laws

General Law No. 26702 of the Financial and Insurance Systems (Ley General del Sistema Financiero y del Sistema de Seguros y Orgánica de la Superintendencia de Banca y Seguros, Spanish, amended through 2009) sets forth the regulatory and supervisory framework for SBS, as well as companies operating in the financial and insurance systems in Peru, including those carrying out activities in the microfinance sector. The law regulates commercial banks and three specialized types of financial entities, defined therein, that engage in microfinance services: (1) municipal savings and credit banks (CMACs), (2) rural savings and credit banks (CRACs), and (3) entities for development of small and micro-enterprises (EDPYMEs). The Law includes provisions that:

- Describe in detail common provisions applicable to financial and insurance companies, including incorporation, license, liquidation and other authorization mandatory for companies operating in these businesses;

- Prescribe guidelines for entities operating in the financial system, including prohibitions, operations and the types of companies falling under this system; and

- Provide guidelines for entities operating in the microfinance sector, which include definition of companies that can engage in microfinance services (Article 282), minimum capital requirements for these institutions (Article 16) and operations permissible for such entities.

Client protection Laws

Código de proteccion y defensa del consumidor. Ley 29,571 of 1 Sep 2010 is the latest revision and consolidation of Peruvian consumer protection law initially in force on 24 Nov. 1992. Código de proteccion y defensa del consumidor. Ley 29,571 Ley 29,571 expressly derogates a number of earlier laws on consumer protection, including Decreto supremo 6-2009/PCM of 2009, unified text in force which includes Decreto legislativo 716.

Article 24 Under Law Decree 716 - In any commercial transaction in which consumer credit is granted, the provider is required to previously report as follows:

a) The spot price of the good or service in question;

b) The initial charge;

c) The total amount of interest and the effective annual interest rate;

d) The amount and details of any additional charges, if any;

e) The number of contributions or payments to be made, the frequency and timing of payment;

f) The total amount to pay for the product or service, which may not exceed the spot price plus interest and administrative costs;

g) The right of consumers to liquidate the loan balance, with the consequent reduction in interest and a statement of charges and costs of this operation for the consumer. (Text added by Article 18 of legislative Decree No. 807)

When a bank or financial institution extending credit to consumers will be forced to previously reported data referred to in subparagraphs b), c), d), e) and g) of this article. (Text added by Article 19 of legislative Decree No. 807)

Transparency resolution

SBS has enforced the transparency resolution 1765/05 to regulate in details how price information must be disclosed to clients and the general public, with an emphasis on interest rates. The resolution has three major elements: customer service infrastructure, information and disclosure, and fair contractual terms between clients and providers. In addition, it also encloses specific rules for the insurance sector, given the nature and complexity of insurance products.

The transparency resolution is applicable to institutions licensed by SBS and gives SBS broad regulatory and enforcement authority as well as sanctioning powers, in a number of issues ranging from transparency to service quality.

There are no caps on interest rates, duties and fees charged by financial institutions, but financial contracts must contain all relevant information on how and when a fee will be charged. Disclosed interest rates (loan rates and remuneration of deposits) must be all-inclusive (effective) and annualized. Updated prices, terms and conditions (if applicable) must be published in well-known newspaper and be permanently and visibly displayed in branches and on the provider’s web site.

All licensed and supervised deposit-taking institutions except of member-only credit cooperatives, are insured by a deposit protection scheme. Apart from that, the fund protection in non-bank-based prepaid instruments, such as e-money service, does not yet receive regulatory treatment neither are nonbank branchless schemes currently operating in the country.

Data Protection & Privacy Laws

The Department of Commerce released an English translation of Peru’s Law for Personal Data Protection (Ley de Protección de Datos Personales, Ley No. 29733). The law passed Peru’s Congress on June 7, 2011, and was signed by the president July 2, 2011. Peru’s adoption of this new law is in keeping with a recent trend in Latin America, where Uruguay, Mexico and Colombia also have complemented privacy legislation.

For all purposes of this Law, for example, the following will have the meaning indicated:

- Personal data: any information on an individual which identifies or makes him identifiable through means that may be reasonably used.

- Sensitive data: personal data consisting of biometric data, data concerning the racial and ethnic origin; political; religious; philosophical or moral opinions or convictions, personal haits, union membership and information related to health or sexual life.

- Personal data database: organized set of personal data, automated or not, regardless of the medium, be it physical, magnetic, digital, optical or others to be created, regardless of the form or modality of their creation, formation, storage, organization and access.

- Sources accessible to the public: personal data databases publicly or privately administered, which may be consulted by any person after paying the corresponding fees, if applicable. The sources accessible to the public will be determined in the regulation.

- Anonymization procedure: processing of personal data that prevents the identification or does not make the data subject identifiable. The procedure is irreversible.

The law builds on guiding principles that closely reflect traditional fair information practices;

- Principle of legality: the processing of the personal data will be done according to the provision of the law, compiling personal data by fraudulent, unfair or illegal means is prohibited.

- Principle of consent: the data subject must give his consent for the processing of personal data.

- Principle of purpose: personal data must be compiled for a determined, explicit and legal purpose.

- Principle of proportionality: any personal data processing must be adequate, relevant and non-excessive for the purpose for which the data were compiled

- Principle of quality: personal data must be truthful, accurate and as far as possible, updated, necessary, pertinent and adequate for the purpose for which they were complied. They must be kept so as to guarantee their security and only for the time necessary to achieve the purpose of processing.

- Principle of security: the personal data database controller and the data processor must adopt the necessary technical and organizational measures to guarantee the security of the personal data.

- Principle of availability of recourse: any data subject must have the administrative and/or jurisdictional channels necessary to claim and enforce his rights when they are violated by the processing of his personal data.

- Principle of adequate level of protection: in the case of trans-border personal data flow, the receiving country must have a sufficient level of protection for the personal data to be processed or at least comparable to that provided by this law.

The law also includes rights to the data subject:

- Right to information: the data subject has the rights to be informed in detail, simply, expressly, unequivocally and prior to compiling, about the purpose for which his personal date will be processed; who will be or who may be the recipients, the existence of the database in which they will stored, as well as the identity and address of the controller and, if applicable, the processor of his personal data; the mandatory or optional character of his answers to the questionnaire proposed to him, especially concerning sensitive data, the transfer of personal data; the consequence of providing his personal data and of his refusal to do so; the time during which his personal data will be kept; and the possibility to exercise the rights granted to him by law.

- Right of access: the data subject has the right to obtain information processed about him in publicly or privately administrated databases, the way his data were compiled, the reasons for their compiling and at whose request the compiling was done, as well as the transfers or planned to be made of such data.

- Right to prevent the supply: the data subject has the right to prevent the data from being supplied, especially when it affects his fundamental rights

- Right to objective processing: the data subject has the right not to be a decision with legal effects on him or affecting him significantly, supported, only be a processing of personal data intended to evaluate certain aspects of his personality, unless it occurs within the negotiation, execution or performance of a contract or in case of evaluation with purposes of incorporation into a public entity, pursuant to the law, without prejudice to the possibility of defending his point of view for the protection of his legitimate interest.

Peru’s new law also:

- Impose specific requirements for data processing by organizations. For instance, special measures will be enacted by regulation for the processing of the personal data of children and adolescents as well as for the protection and guarantee of their rights. For the exercise of the rights recognized by this Law, children and adolescents will act through their legal representatives, whereby the regulation may determine the applicable exceptions, if appropriate, taking into account the superior interest of the child and adolescent.

- Create a data protection authority, the National Authority for Personal Data Protection, which exhausts the administrative channel and allows for the imposition of the administrative sanctions provided in article 39 of this law. The National Authority is funded by registration fees, fines, bequests and donations, resources obtained through international technical cooperation, and resources made available by law.

- Establish a National Register of Personal Data Protection to record (1) publicly or privately administered personal databases, (2) authorizations issued pursuant to the data protection law, (3) sanctions imposed by the National Authority, and (4) codes of conduct of the entities representing the privately administered personal database controllers or processors.

Conclusion

The regulatory and supervisory framework for financial consumer protection in Peru is well advanced, which gives SBS a range of power to enforce such rules and impose sanctions in the case of noncompliance. With regard to regulatory measures affecting branchless banking, there is room to boost through regulation on transparency. It is also necessary to gather better complaint information to effectively identify and deal with problems faced by credit users. Pertaining to areas that are not directly linked to consumer protection, more efficiency and interoperability in retail payment system would facilitate the use of agents and the ease of access to payment services by users from all income levels, which are a necessary step for faster and effective financial inclusion.